C compilation and execution

Index of Topics

C compilation and execution

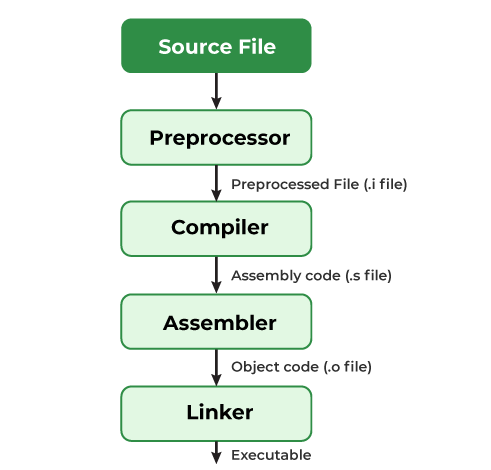

Steps

1. Preprocessing

- The preprocessor (part of the compiler) processes the source code before actual compilation.

- It handles directives such as #include, #define, and #ifdef, expanding macros and including header files.

- Preprocessing eliminates comments and replaces macros with their respective definitions.

2. Compilation

- The preprocessed code is passed to the compiler, which generates assembly code specific to the target architecture.

- The compiler performs syntax and semantic analysis, checking for errors and generating object code.

- The output is an object file (often in a binary format like ELF) containing machine code and unresolved references to functions and variables.

3. Linking

- The linker takes the object file generated during compilation and resolves the unresolved references.

- It resolves function calls and variable references by searching for their definitions in other object files or libraries.

- The linker generates an executable file, combining the object file with any necessary library code.

- If there are unresolved references, it will result in a linker error.

4. Loading

- The operating system’s loader takes the generated executable file and prepares it for execution.

- The loader allocates memory to hold the program’s code, data, and stack.

- It resolves external dependencies and performs necessary address relocations.

- Finally, it transfers control to the program’s entry point (typically the main function).

5. Execution

- The program’s code is executed by the processor, following the instructions in the machine code.

- Global variables are initialized, and the program begins executing statements within the main function.

- The program may interact with input/output devices, perform computations, and call other functions as needed.

- Once the main function completes or encounters a return statement, the program terminates, and control is returned to the operating system.

Memory Addressing

- Typically even though you may have a 64 bit machine. The address space is only going to be 48 bits

Static Keyword

There are two uses for the static keyword

1. On a Function

- When used on a function, it tells the compiler that the function is only accessible from the current file.

1

2

3

4

5

int myFun1(int a, int b){

int c;

c = a + b;

return c;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

#include <stdio.h>

// function from external.c

int myFun1(int a, int b);

int main(int argc, char const *argv[alt-text]){

int result = myFun1(1, 3);

printf("result = %d\n", result);

return 0;

}

- We would be able to run this no problem with

gcc external.c main.c - But if we instead changed external.c to make the function static like this

1 2 3 4 5

static int myFun1(int a, int b){ int c; c = a + b; return c; }

- And ran the same

gcc external.c main.c, we would get an error like this1 2 3

/usr/bin/ld: /tmp/ccNF13g3.o: in function `main': test.c:(.text+0x1e): undefined reference to `myFun1' collect2: error: ld returned 1 exit status

2. On a Variable

- There are 2 ways to use the static keyword on a variable

- Static Storage Duration:

- By default, variables declared within a function have automatic storage duration, meaning they are created when the block is entered and destroyed when the block is exited. However, when the static keyword is used with a local variable within a function, it changes the variable’s storage duration to static. This means that the variable is initialized only once, and its value is retained between function calls. The variable exists throughout the entire program’s execution.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

void myFunction() { static int counter = 0; counter++; printf("Counter: %d\n", counter); } int main() { myFunction(); // Counter: 1 myFunction(); // Counter: 2 myFunction(); // Counter: 3 return 0; }

- File Scope:

- When static is used with a global variable (declared outside any function), it restricts the variable’s visibility to the file in which it is defined. The variable cannot be accessed by name from other source files using the extern keyword. It effectively limits the variable’s scope to the translation unit (source file) where it is declared.

1

static int globalVariable = 42;

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

#include <stdio.h> /* This will fail because static is used on the variable in external.c If you wanted this to work you would have to remove the static keyword before initialization in external.c before the globalVariable */ extern int globalVariable; int main() { printf("Global variable: %d\n", globalVariable); return 0; }

- Static Storage Duration:

Header Guards

- They are used to tell the compiler to include and define certain snippets of code. This is important so that way code from a file isn’t included more than once.

- I know what you’re thinking, I would never include code from another file twice?!?

- But it is easier than you think when you work with multiple files

- Example.

- A includes B

- B includes C

- A includes C

- In this scenario if we did not use a #indef, then we would accidently include the C file twice because A includes it directly and indirectly because A includes B which itself includes C

- Example.

Casting

There are two types of casting

- Implicit casting

unsigned char my_variable = 0xFF + 0x11;

- This will perform the addition which is 0xFF + 0x11 = 0x110

- But this will truncated to 0x10 which is 16 in decimal

- Explicit casting

unsigned char var = (unsigned char) (0xFF + 0x11);- This is doing the same casting except explicitly

C Tools

List of some of some helpful C Tools

- gdb

- valgrind

- binutils

- objdump

- readelf

- strings

- strip

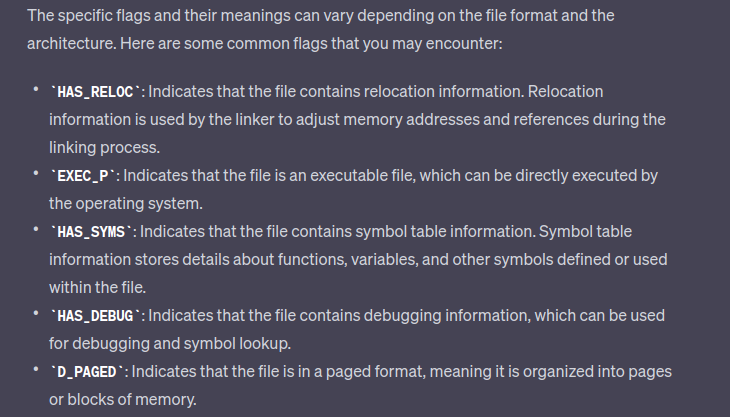

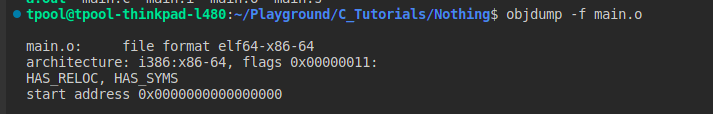

Objdump

Getting information about a file

objdump -f <filename>

- The last line specifies the start address

- for an object file it will be 0x0 because it hasn’t been linked therefore it doesn’t know where the start address will be

- for an executable it will be populated with a 64 bit hex memory address that contains the start of the program in memory when it gets loaded

objdump -s <filename>- Gives the executable data separated by sections

objdump -d <filename>- This will dissasemble the executable into the assembly code

readelf --segments <filename>- This will display the logical segments of memory for you program

strip <filename>- This will strip all of the debug information and symbols from the executable

- Makes the executable smaller

- Also makes it harder to debug and reverse engineer

- This will strip all of the debug information and symbols from the executable

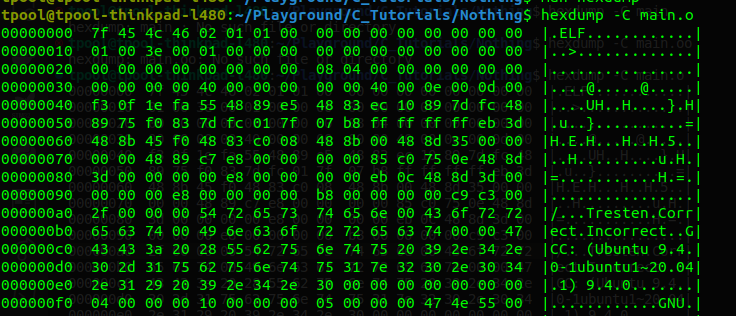

Hexdump

Printing out the binary in characters

hexdump -C main.o

To edit one of these files you can use vim

vim -b main.o:%!xxd- this will give you the same view as

hexdump -C main.o, except now you can edit the hex

- this will give you the same view as

:%!xxd -r- this will take back the binary to it’s original format

:wq- makes sure to save the file

References

- Memory Addressing

- Static keyword

- Header Guards C Tools

- Objdump

- Hexdump

- <iframe class=”embed-video youtube” loading=”lazy” src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/bWMIpHVRFUo” title=”YouTube video player” frameborder=”0” allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen

</iframe>

This post is licensed under CC BY 4.0 by the author.